How to Decide if it’s Time to Move on with Grammar

Tired of wondering? How do you know when it’s time to move on with grammar instruction? This post will provide you with five important ways to make a confident decision.

When should we move on with a grammar concept and when does it need to be re-taught? Making this decision requires reflection, strategy, and knowledge of best practices. As with everything else in education, this question has many possible answers. Teaching grammar can be tricky, but when students’ best interests drive our instruction, it’s hard to go wrong.

So, let’s address this question of when it’s time to move on with grammar by starting at the beginning. If we have confidence in our lessons, we will feel better about whether or not students have walked away proficient with important grammar skills.

TEACHING GRAMMAR: WHERE TO BEGIN

At the beginning of the year, I give students a comprehensive grammar diagnostic. And, at the start of an individual unit, I like to start with a smaller diagnostic so that I have an indication of students’ current understanding and a way to track growth. No Red Ink has some diagnostics that focus on specific details, but when I want a bigger picture of whether my students can transfer those skills to writing, I create my own.

From there, I begin with direct instruction in the form of a mini-lesson. Research has proven that direct instruction rooted in best practices can improve students’ writing abilities and understanding of language (especially when it focuses on targeted skills identified by common writing errors). However, conducting a mini-lesson requires strategy.

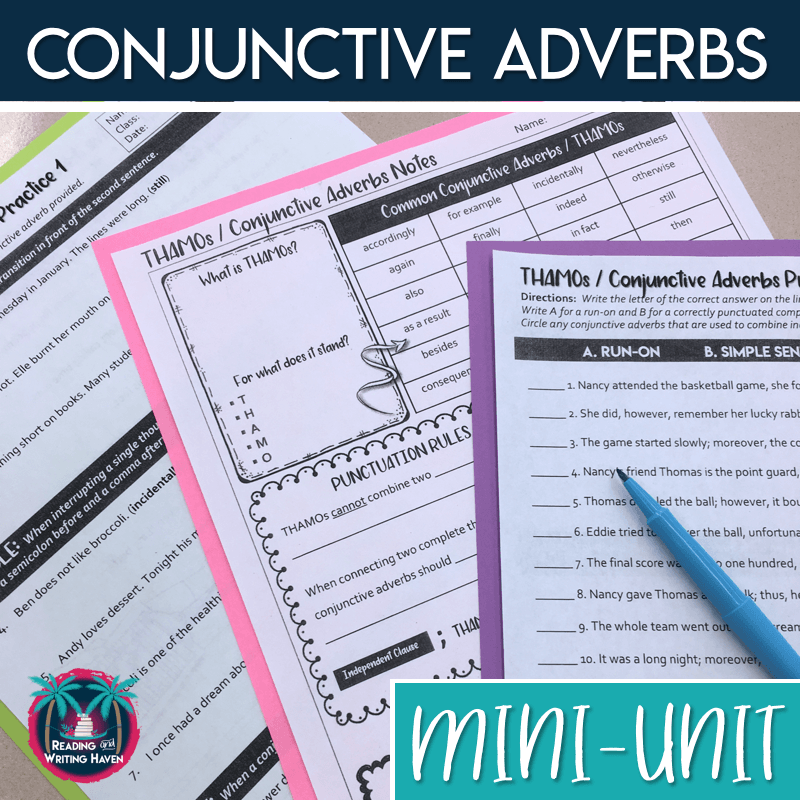

When considering if you should move on or reteach a concept, it’s important to reflect on how you chunked the direct instruction. For example, when I teach conjunctive adverbs, I break the lesson down into three (or four – depending on my students’ readiness levels) separate lessons. We discuss how they can be used in the front, middle and back of a sentence to add variety. Each day for several consecutive days, we study one of those approaches. It seems to be more effective to chunk direct instruction in this manner rather than introducing multiple skills in one day.

MOVING STUDENTS FROM GUIDED PRACTICE TO INDEPENDENCE

After teaching each use for conjunctive adverbs, we do some whole class practice exercises. I then move students to group activities and then to independent work. Can they do it on their own successfully? If so, it might be time to assess them. Usually, however, some students show early understanding of the topic, and others are still confused.

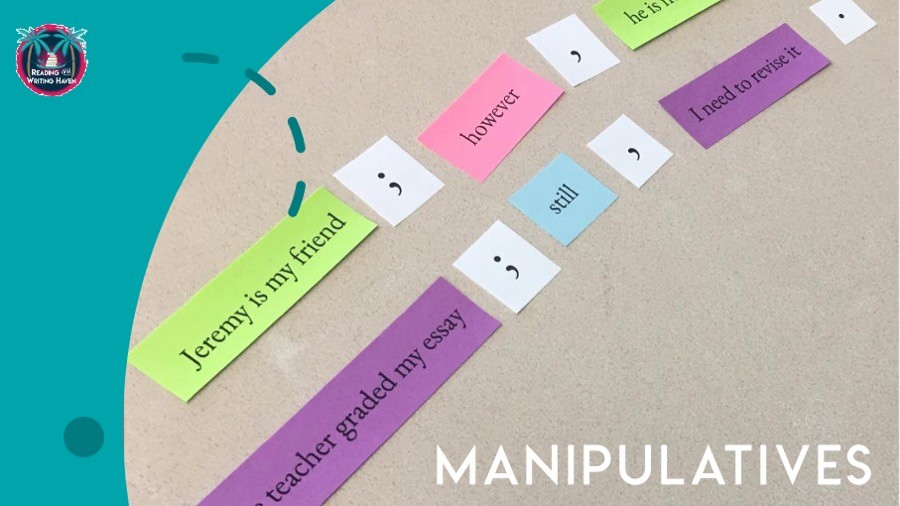

When this is the case, I work on focused, small group instruction with the latter group. My favorite way to do this is in the form of a visual or kinesthetic activity.

Of course, there’s always the rest of the class. What are they doing? I try to stick to something simple but make it worth their time. Enrichment activities might include…

- asking students to read a novel of their choice and look for examples of how the author uses that grammar skill (or how/why he or she breaks the rule).

- having students apply their knew grammar knowledge by adding it into their most recent essay.

- writing a collective piece in small groups in which students use the new grammar skill and check one another’s work.

REFLECTING: IS IT TIME TO MOVE ON?

After informal interventions, I give students a post-assessment. It looks very similar to the pre-assessment, but the questions are slightly different. Same skills…different words. If 80 percent of students show mastery on a grade-level skill after I’ve tried all of the aforementioned approaches, we move on.

It’s important that you talk about that number with your department. Does 80% make sense to you? Would another number be better?

A few considerations…

Other than feeling confident you’ve done your best with a solid instructional unit (read more in this post about how to teach grammar or this one about structuring grammar lessons), let’s consider some additional reflection points for whether or not it’s time to move on with grammar.

1. Look at the learning continuum.

Often, a grammar skill is built upon over the span of multiple grade levels. According to the Common Core standards, middle school students are expected to write in complete sentences and to use various types of sentences, but students aren’t expected to master the semicolon until high school (grades 9 and 10). When deciding whether you should move on or re-teach a skill, keep in mind the specific grade-level standards for your course.

2. Consider spiraling.

Will this skill be one that your students come back to throughout the year? Each grade level emphasizes different grammar skills.

- Sixth grade? Highly intensive with pronouns.

- Seventh grade? Punctuation and sentence structure are huge.

- Eighth grade? Students need to know verb moods and verbals.

- Ninth grade? Parallelism, types of phrases and clauses, semicolons, and colons.

The list goes on. So, when considering whether or not to move on, we need this knowledge. If you move on and a large portion of your students haven’t mastered these very important, foundational grammar concepts, it will result in language and writing gaps as they move on to the next grade level.

If you move on, however, knowing it’s an integral piece of your grammar instruction that you will continue revisiting all year, students will have more opportunities to learn. That’s good!

If your ninth grade students STILL haven’t mastered the eight parts of speech, it doesn’t hurt to review, but it shouldn’t be where we spend the majority of our instructional time.

3. Look at students’ writing.

Is it time to move on with grammar? Look at students’ writing. Is the lack of grammar knowledge directly impacting the proficiency of their writing? If so, stick with it. Continue trying to draw important connections between mentor sentences (how and why authors use these grammar concepts) and students’ own writing. The more we can integrate our instruction, the quicker students will learn these skills.

However, if a students’ lack of proficiency with verbals – for example – isn’t directly impacting their writing abilities, it’s probably not necessary to spend weeks on the concept.

4. Is it an essential skill?

Deciding whether it’s time to move on with grammar is largely related to three things:

If you move on too soon, will it…

- cause students to fall behind with the next step for your own course? In other words, in your class, will a gap in their knowledge with this one skill cause them to continually fall further and further behind?

- result in issues with other classes they are currently taking or that they will take in the future? For instance, many other subject areas expect older students to write in complete sentences and use proper quotation marks for quotes.

- translate to difficulties in life? In other words, will their lack of grammar knowledge result in eating Grandmas? If so, it might be necessary to stay the course until all Grandmas are safe. (Side note: This is both a joke and a pop culture reference.) But, will it be an issue for them in creating a resume, email, or other career-type communication?

5. Ask your students.

I’m a huge believer in allowing students’ voices to drive instruction. If you’re not sure whether students are ready to move on with a grammar concept, ask them to self-assess.

Can you do this work independently? Can you do this work with some guidance? Or, are you still confused by this skill and feel more comfortable with me using this grammar concept as I write alongside you?

We can combine what we know about our students with their self-assessments to make a well-informed decision moving forward.

As always, there is more than one way to teach ELA. If you’re looking for an alternate perspective, Lauralee at Language Arts Classroom is sharing tips for teachers who are new to grammar instruction.

WHAT TO READ NEXT:

- Why Teach Grammar?

- How Do I Sequence Grammar Instruction?

- How Do I Structure a Grammar Lesson?

- Spicing Up the Grammar Lesson

- Differentiating the Grammar Lesson

RELATED RESOURCE:

This conjunctive adverb mini-lesson is the one I use to scaffold and chunk instruction to maximize my students’ growth from beginning to end of the lesson (as described in this post). You can find more of my grammar units here.

[sc name=”mailchimp1″]