How to Structure a Powerful, Meaningful Vocabulary Program

Inside: A fresh, powerful way to structure a meaningful vocabulary program for middle and high school students. Vocabulary instruction should be more than an afterthought! Read about making it an integral and enjoyable part of your course as well as how to increase retention.

In order to structure a powerful vocabulary program, we need to tear down our existing walls and reconsider our purpose. This vocabulary structure is for you if you want…

- vocabulary to be fun and engaging

- learning new words to inspire students

- word study to be an integral part of your course

- vocabulary words and activities to be relevant to students

- students to recognize vocabulary words in books and use them in writing

I’ve written a whole manual about effective vocabulary instruction, but this post is my most recent, and it’s full of ideas you can use to add meaningful, unexpected twists to your traditional lessons. In this post, I’m synthesizing many of my findings about common questions regarding meaningful vocabulary.

PILLARS TO MEANINGFUL VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION

Make it a Routine

How often do I need to teach vocabulary in order for students to retain the words?

Daily. Or, as often as possible. When I first began teaching, it was common practice to assign 20 words on a Monday along with a packet of worksheets for practice. Students would have a quiz on Friday. Clearly, this approach is neither inspiring or effective.

If we want students to truly retain new words, we have to build them into our daily routines. If the structure of your curriculum or the time constraints of your class periods won’t allow for daily practice, then you have a couple of reasonable second options.

- Build in vocabulary work three times a week instead of five.

- Pair vocabulary with reading units and grammar with writing units.

In order to make vocabulary a routine, that doesn’t mean students have to complete the same type of activity every day. That sounds mundane! By routine, I just mean that students are used to word study as a valuable part of the class culture. They enjoy the frequent opportunities to be curious about words and to…well, befriend them!

Examples

Let’s take a look at some possibilities for vocabulary routines:

- introduce a new word each day, but make sure to allow some time for spiraling in words from old units and for review

- introduce five new words on a Monday, and then build in differentiated practice activities and games with whole-class, individual, or learning station formats

- use daily vocabulary bell-ringer activities as opportunities to make brain-based connections with their vocabulary words

- every time students write (in response to literature, an essay, a RAFT, etcetera), ask them to build in a certain number of their vocabulary words

- keep a student-generated word wall that you can use as inspiration for quick vocabulary practice (Ex. – Find two words on the word wall that don’t seem to fit together and make an unusual connection between them!)

- regardless of how they are introduced, be intentional about using the vocabulary words in class discussions and asking students to use them in their speaking (quick vocab conversations are a great use of transition time!)

When we take time to give students high-interest repetitions that involve complex thinking and connections, we are creating a meaningful vocabulary structure that sets students up to retain – instead of memorize! – new words.

Keep it Fresh

While routines are important in terms of prioritizing vocabulary learning, in order to capture middle and high school students’ attentions, we still need to keep instruction fresh.

There’s nothing wrong with switching up the types of lists and practice activities we provide for students throughout the year. Here’s an example of a handful of different approaches for incorporating vocabulary:

- During short story and poetry units, use high-frequency words from literature.

- During writing units, focus on vocabulary for formal word choice.

- With independent reading units, try a word-a-day approach with context clue practice.

- Spend a couple weeks toward the beginning of the year introducing students to word parts.

- Study the connotation of language in children’s picture book mini lessons.

- And, don’t be afraid to teach students how to create their own vocabulary lists!

Meaningful vocabulary programs should not be boring or feel like a chore. They should inspire us to love learning about words. After all, words are the way to readers’ and writers’ hearts.

Choose Relevant Words

What’s better – using words from literature or those on a high-frequency list?

When choosing words for vocabulary instruction, I think sometimes we get too caught up in the details. While it does matter to some degree, I don’t think where the words come from is as important as why we are asking students to learn them.

I agree that when teaching literature, we need to frontload whole-text experiences and build background knowledge by introducing important words. The question is, however, what do we deem important?

One of my most important rules of thumb is to limit new words to five per week (and even that number may be a bit much for distance learning situations). One of the issues we run into with literature is selecting too many words! And, what about technical words? Should we include those?

Words I wouldn’t include on a vocabulary list…

Technical words – By this, I mean words that are very specific, non-high-frequency words, like the name of a specific mountain chain, scientific terms in an informational text, or subject-specific jargon. I generally do not include these words on a vocabulary list. Instead, I use these words to teach context clue work or word parts. I model how to use context clues to determine a technical word’s meaning as well as how to use a reference source to verify my initial prediction. Then, students practice with other, similar words. Or, show students how to break down unfamiliar subject-specific words by recognizing word parts.

Obscure words – Some words are obscure. That is, they might not be technical words, but they are words that aren’t used often. I find little value in teaching students words that won’t help them to be successful in reading, writing, or life. The word farrago, for example? It just means hodgepodge. I wouldn’t teach that. But, while reading a short story with students, if we came across it, I would gladly define it for them to scaffold their understanding of the text. I have included some fun, obscure words into language activities before…encouraging students to use context clues and work on grammar concepts at the same time, but I wouldn’t expect students to remember or use those words. They’re just for fun!

How I choose words for a vocabulary list…

There are several factors we can consider when choosing words for a vocabulary list.

Integral

If using words from literature, let’s choose words that relate to the core literary elements for that text. Take “The Interlopers,” for example. The word interloper would be important for discussing the conflict of the story. Compact, quarry, plight, and condolences would also be key vocabulary words because students would use those in their analysis of the text. Sylvester night, skirling, and roebuck could potentially be vocabulary words as well, but their significance to the story overall is far less. We can just discuss those with students as we read.

Relevance

Are the words we are selecting relevant to students? Might they encounter those words in a book or while listening to a Ted Talk or podcast? Would they use the words in writing? Can they make connections with the words in order to make their learning sticky? Can we find an intriguing way to introduce these words to students to make the learning experience high interest? (See 10 examples.)

Relational

Can we use the words to help students understand morphological word families? We could talk about adverse, adversity, adversary, and adversely, for instance. Each of these words has a unique part of speech and a slight difference in meaning, yet they are all related to the same root word.

Along the same lines, when writing about an adversary, what other new words might help to deepen students’ relational level with the word? Belligerent? Antagonistic? Detriment? Think about what related words in the same definitional word family students might be likely to use with while writing or what collocates (juxtaposed words) they may see while reading.

Tip: Avoid including synonyms in the same vocabulary lists, if possible (example – abase and berate). Students often find that confusing! However, you can always spiral in words from previous units to help students make synonym-type connections throughout the year.

Use Creative Activities

No matter what type of word list we are using, a powerful, meaningful vocabulary program is often full of activities that encourage creative thinking.

Help students to connect with their words by involving them kinesthetically.

- skits

- Truth or Dare

- charades

- sculpting

Show students how to personify a word.

- speed dating a word

- sticky words game

- task cards – print or digital

Give students opportunities to use the words in creative writing.

- RAFTS (role, audience, format, topic)

- 6 room poems

- social media captions

Help students visualize the words.

I’ve written several posts about brain-based vocabulary activities that add value to the learning experience! You can find them here.

Differentiate Naturally

Does differentiation with vocabulary mean I have to provide sixteen different vocabulary lists?

Goodness, no! Now, there isn’t anything wrong with providing students with tiered vocabulary lists, but we should only do what is manageable for us at any given point in time. A different way to differentiate vocabulary words is to vary the depth of knowledge we want students to show.

Level 1 – Unistructural

For example, we often begin with just the definition. Can students use context clues to determine word meaning? Then, can they verify the definition in a reference source? But, we can’t stop here! Often, that’s what happens with memorization, and because students haven’t moved beyond this superficial level, they don’t retain the word meaning.

Level 2 – Multistructural

Have students study antonyms, synonyms, and word parts. What word family does this word belong in? When students begin to make multi-level connections with their words, they slowly expand the depth of their knowledge.

Level 3 – Relational

Students may be ready to make connections. Pictionary and association sketches are a common way to do this. Can students create a web, sketch notes, or mind map showing the connections between this word and its deeper meaning or between this word and other vocabulary words? Can they complete or create analogies and categories for the word?

Level 4 – Extended Abstract

Extend students’ thinking to an abstract level. Students can get to know this word as a friend. What does it like? Dislike? What are its dreams? What does it do for fun on the weekends?

Another way to extend thinking is to prompt students to transfer their learning. How can a word like synthesis, for example, be applied both in science and ELA classes? What does the word have in common across contexts? And, the word dynamic could be applied to character development, music, physical education, and economics. Whenever possible, building in opportunities to transfer words to other contexts deepens understanding and elevates the learning experience.

As mentioned earlier, we can also differentiate for students by offering them choices in how they want to learn their words. Having a solid collection of fun, creative activities and prompts will make for meaningful vocabulary practice.

Assess Authentically

Meaningful vocabulary programs include meaningful assessments. What’s the best way to assess students’ vocabulary acquisition?

The answer to this question depends on the goal, but in a word – authentically.

If we want students to use their words in writing, we should ask them to do so. In addition to giving students formal and informal writing assignments, we can have students show their growth formatively during classroom stop and jot transitions.

If we want them to use the words in speaking, let’s have a short conversation with them. (Ex. – Tell me about what you are going to do after school tonight, and while you are talking, please use all five vocabulary words. Be sure to add in enough context so that I can tell you know what the word means!) In just a few minutes, we can tell whether or not students truly understand their five new vocabulary words.

If we want students to explain what a word means in context or how its connotation impacts the mood and tone of literature, we could give them a short excerpt and have them analyze the impact of bolded words.

We can give multiple choice vocabulary quizzes to check for basic understanding, but it’s helpful to build in some authentic, higher-level assessment elements as well.

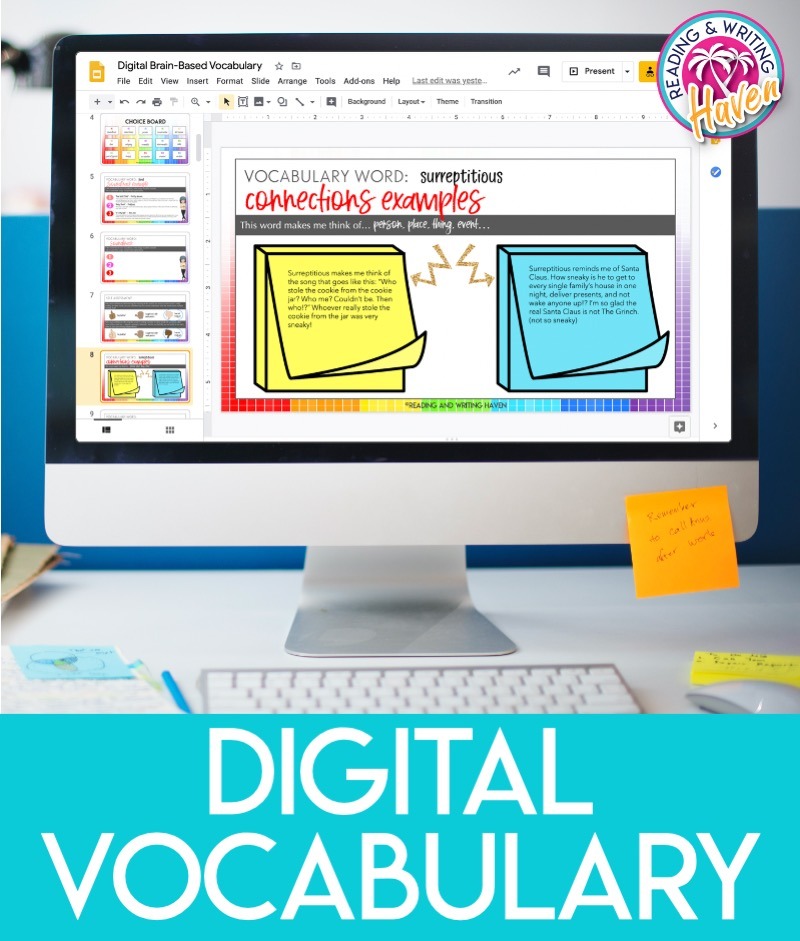

Digital Considerations

Meaningful vocabulary instruction may look a little different with online teaching. Distance learning naturally forces us to scale back what we are teaching. Maybe students only learn three new words instead of five! In order to prevent vocabulary from feeling like an afterthought with online instruction, we should look for ways to build it into regular routines (and into the rest of our curriculum).

Videos

Why not give students a short, five minute video to watch at the beginning of the week? Maybe you spend one minute introducing each of the five new words. Students can create videos, too!

Conversations

Pose a few vocabulary-centered, interesting questions on Flipgrid or your favorite online discussion platform (written or verbal), and ask students to respond to one of the questions. Their goal should be to continue the conversation, which means they need to listen to or read the comments left before theirs in order to build upon them.

Check-Ins

If you use online check-ins, ask your students to use one of their vocabulary words in their responses.

Writing

When writing about reading, ask students to incorporate new words.

Grammar

Have your language study do double-duty by writing your own sentences that contain vocabulary words or by using mentor sentences from literature that contain the new words.

Reading

Show students how to select vocabulary words that are a good fit for them from their independent reading books. They can keep an ongoing list of words they want to understand better, which encourages metacognition.

Quick Digital Practice

Students can complete graphic organizers and quick digital practice activities online to elevate their thinking.

Technology

Online websites like Quizlet (which now has a remote live feature!), Gim Kit, Vocabulary.com, and Flocabulary (subscription required) are high-interest ways to engage students in vocabulary instruction remotely.

When it comes to formally assessing vocabulary with online learning, I think there will naturally be less of it, and that is okay. We can teach students how to self-assess and monitor their own learning, and we can dedicate assessments to the specific skills inherent in the vocabulary standards.

Meaningful vocabulary instruction should be more than just an afterthought. If you feel like you have never really loved your approach to teaching vocabulary, I encourage you to start plugging away at some of the ideas in this post. This approach is fresh, powerful, and inspiring. Figure out what fits your teaching style and what resonates with students. Most of all, make sure you are having fun! If vocabulary is enjoyable, it will be memorable, which is the ultimate goal.

VOCABULARY ACTIVITIES

These brain-based, differentiated vocabulary activities can be used with any word list and are sure to engage middle and high school students in meaningful, thought-provoking word work.