Lesson Planning Tips: Content Chunking

An important element of effective lesson design is content chunking. Often, it gets side-stepped due to time constraints or a push to get through the material faster. When teachers prioritize content chunking, it can increase student engagement. Consider the following conversation I had with an evaluator years ago…that I still remember vividly.

Evaluator: How long do you think you spent on the plot metaphor presentation?

Me: (fairly confidently) Probably about ten minutes. Maybe fifteen.

Evaluator: Actually, it was twenty. Did you intend to spend that much time on direct instruction?

Me: (much less confident) Hmmmm. No, I’m surprised.

It’s interesting how a teacher’s perspective of how class time passes can be much different than that of a student’s. Having a good grasp on our sequence and pacing as well as a solid understanding of student attention spans and the need for frequent review can positively impact instruction.

Sometimes, it helps to have another teacher, evaluator, or coach help us reflect on lesson design. If you’ve never done this, it can be powerful to reach out to someone for specific feedback or to record your teaching so that you can reflect upon it.

WHY USE CONTENT CHUNKING?

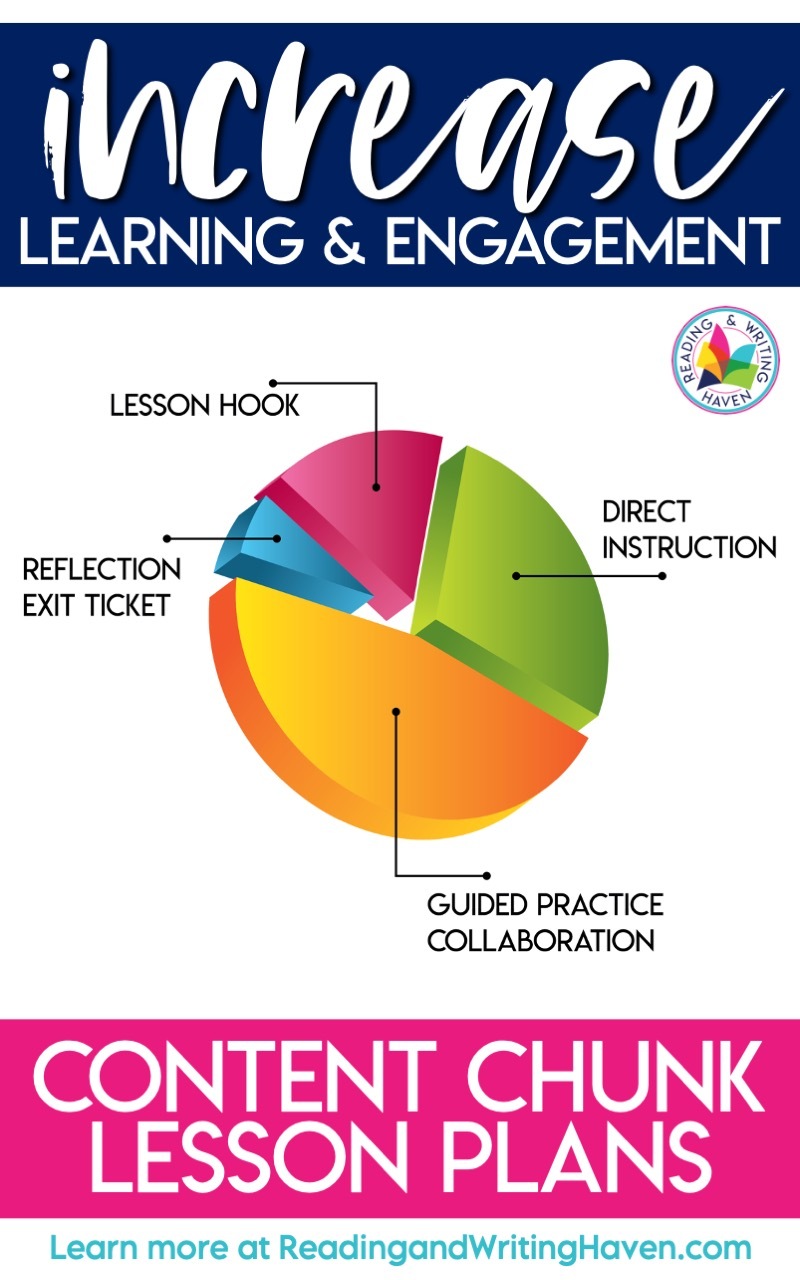

Research shows that students learn material more easily when we practice content chunking. In this post, I’m referring to content chunking as two different things, but both equally important:

- breaking down course content and skills into smaller chunks that are more easy for students to digest

- chunking the class period strategically to increase mastery of content

When done effectively, students comprehend the content better, learn more of it, and remember it longer. Content chunking gives students time to really dig into a skill, idea, or concept long enough that they can appreciate it, reflect on it, and connect with it at a deeper level.

Middle school students, in particular, are typically only able to focus for 10 to 15 minutes at a time. High school? 15-20. Research also suggests that in order to increase learning, students need multiple review opportunities within a class period, not just one at the end. Content chunking is a great way to address both focus and mastery issues.

What’s more, content chunking provides opportunities for students to get up and move. Increased blood flow and oxygen are beneficial for learning. And, if you chunk the content, you’re able to provide different learning styles and formats for students.

So, let’s look at some examples of how you might practice content chunking without making a class period feel like it’s full of a bunch of isolated activities. How can content be chunked so that it builds throughout the lesson?

LESSON DESIGN EXAMPLES…

Character Development

Let’s say you want to introduce an important topic, like integrity. You may choose to begin with a hook, maybe a video. The video may naturally lead into a turn and talk experience where students come up with a working definition of integrity.

After having time to talk with a partner, you may decide to engage students in a whole-class discussion. What is integrity, and what qualities comprise it?

Following, you may ask students to create a piece of artwork, like a motivational poster, that represents their view of integrity. Perhaps students post their creations to Seesaw, Padlet, or another visual app that will allow them to see one another’s work and discuss patterns and trends.

Be intentional about the amount of time you want to devote to each element of the lesson.

Sentence Types

Instead of trying to cover simple, compound, complex, and complex sentences all in a day or a week, try content chunking. For example, you might spend a week on each sentence structure.

To chunk sentence type lessons, I’ve had students begin by writing a short (1/2 page) journal response. I usually find an image, cartoon, or controversial statement that evokes emotion. The topic doesn’t matter as long as they write.

Next, we put the journal response away, and I conduct a mini lesson on, for instance, simple sentences. Built into the mini lesson, students will practice applying their knowledge of subject verb patterns.

To mix up the learning styles, I then have students do a manipulative sorting activity.

We wrap up by referring back to the original journal prompt to identify any areas where students used a simple sentence and talk about the flow of their response.

Reading

Imagine you are ready to introduce students to a new reading strategy. Whether it’s a sign post or a skill like summarizing, re-reading, or evaluating a text, you might choose to begin with a mini lesson. Seravallo’s Reading Strategies book has many helpful mini lesson suggestions you could pull from as do the Notice and Note texts.

After your whole-class mini-lesson, you may decide to dive into a workshop-type approach for the remainder of the period. For instance, you might offer students a menu of options.

- Must Do: Read your independent novel. Meet with teacher in your small group to practice today’s reading strategy.

- Should Do: Write about your experiences with applying today’s reading strategy in your readers’ notebook or on a graphic organizer.

- Could Do: Look for examples of this week’s grammar concept and vocabulary in your independent reading novel.

Wrap up class by bringing everything full circle. Review what reading strategy students focused on, why it is helpful, and when to use it. Also, talk about productivity and stamina. How did students work? What new goals or foci will you collectively set for next time? Perhaps, give students an exit slip to determine their skill level with using the strategy from the mini lesson.

Writing

Writing essays is often challenging for students. Sometimes, their overwhelm and confusion simply comes from trying to do too much at once and not having a manageable, bite-sized focus. As a result, a few freeze and don’t write anything at all.

We can use content chunking to address both the class period flow and the tasks we are asking them to do.

Chunk the content by focusing solely on one paragraph at a time, even going so far as to scaffold students’ understanding of each part of a conclusion paragraph. What might this look like in terms of lesson design?

You could begin by reading an exemplary conclusion paragraph with the class. Ask them to brainstorm what makes it successful, and ask them what components a good conclusion paragraph should contain.

After a whole-group discussion, you could move into explicit note-taking on the three essential components for a conclusion paragraph.

Next, give students a few examples, and in small groups (for a different format), have them highlight paragraph components and evaluate each conclusion’s effectiveness.

Finally, give students a graphic organizer and allow them to begin writing their own conclusion paragraph. By this point, they should have a much better understanding of the “how to”. Plus, they won’t be trying to quickly rush through it as an after-thought because the whole essay was assigned at one time.

This is the conclusion paragraph mini unit I use.

Whether you’re looking for fresh lesson design ideas, needing to find ways to help students achieve mastery, or thinking about how to manage the minutes in a class period to increase engagement, hopefully you’ve found some inspiration in this post.

When planning a lesson and a unit, these are some of the approaches I use intentionally. Understanding how the brain works and how students truly learn is an integral aspect to creating lessons that linger.