Reading Instruction: Deciding What to Teach

This post is part of a series about reading instruction. To start from the beginning, read about getting to know your readers.

When teachers plan reading curriculum in secondary, the conversation often centers around what stories we should teach. There’s nothing wrong with discussing literature for different grade levels, but should it be our first question?

Before selecting texts, I think we should prioritize what standards and skills we want to zero in on as we read. How would our lesson planning look different if we asked, “What standards and skills will I be helping students strengthen with this unit?” instead of “What story should I teach?” The first question naturally will lead into a conversation about what literature fits best. The second may result in overlooking what skills students need to work on most.

In the book A Novel Approach, Kate Roberts writes that part of our literature selection needs to take into account which books are best for teaching which skills. For instance, Lord of the Flies is great for understanding figurative language and developing inferring. To Kill a Mockingbird works well to analyze text structure and pacing. Salt to the Sea is ideal for building students’ understanding of character development and point of view.

So, in terms of what we should teach with reading, it really comes down to two things: the standards and the students.

Differentiating Reading Instruction

Regardless of if we teach in a standards-based reporting district, we need to know students’ current readiness with course standards. Sometimes, I find the entire class needs help with meeting the skills required from a standard.

For instance, my students have always shown a need for more skill development with summarizing nonfiction, literary analysis, and inferring. These are all reading behaviors and understandings inherent to the standards. So, those topics make for ideal strategy mini lessons with the whole group. But! Not all students need to work on the same skills.

Reading Teachers are Coaches

What do many athletes and musicians do to improve their skill level? They go beyond playing on a school or recreation league team. Many seek one-on-one lessons or engage in enrichment activities – summer camps or travel teams. It’s important that we allow ourselves to view teaching reading in middle or high school similarly to coaching.

Each student may need different practice, but because of the time constraints of a forty-five minute class, many secondary ELA teachers find it difficult to meet individually with each student several times a week. Consider your schedule. Can you meet with each student once a week? If so, listen to him or her read, or talk about what that student has been reading independently. Then, set a goal to touch base on the next time you confer.

Also, working with small groups using texts appropriate for students’ reading levels and skill needs is imperative. What would happen if we coached a team and never met with individual players or groups of players to hone certain skills? The divide would widen. The same problem is true for reading instruction.

Getting to know our students as readers through conferring and other approaches can help us to differentiate meaningfully. Granted, in secondary, it can be difficult to make time for as many one-on-one student conferring sessions as it is in elementary school. So…

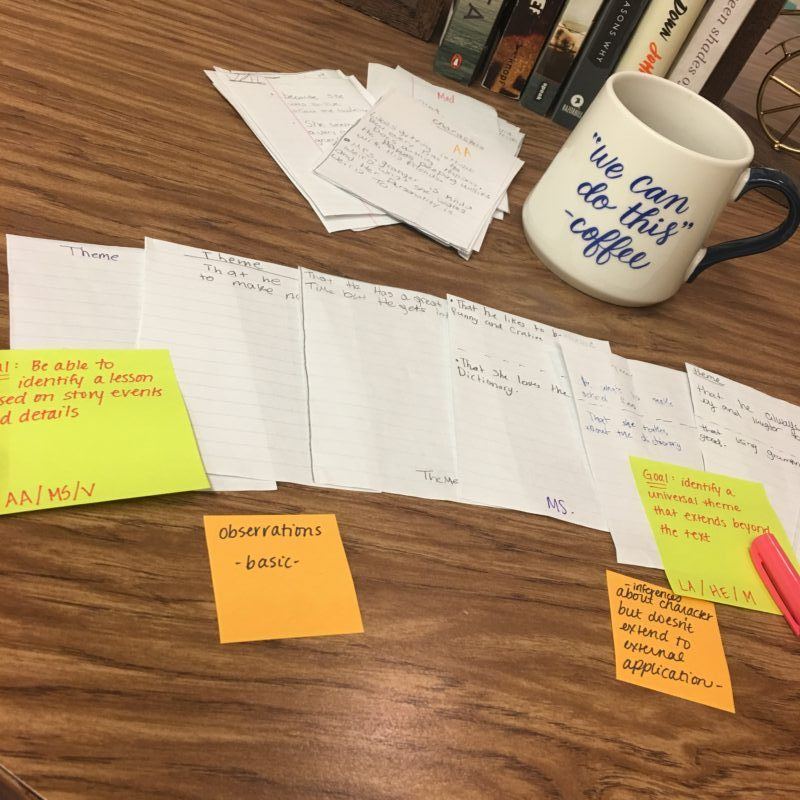

Efficiently Gathering Student Data

One way we can quickly gather information about our whole class as readers in order to create groupings is through jottings. (I’m not advocating that this replace conferring with students, but it is a way to alleviate some of the time constraints secondary teachers experience.)

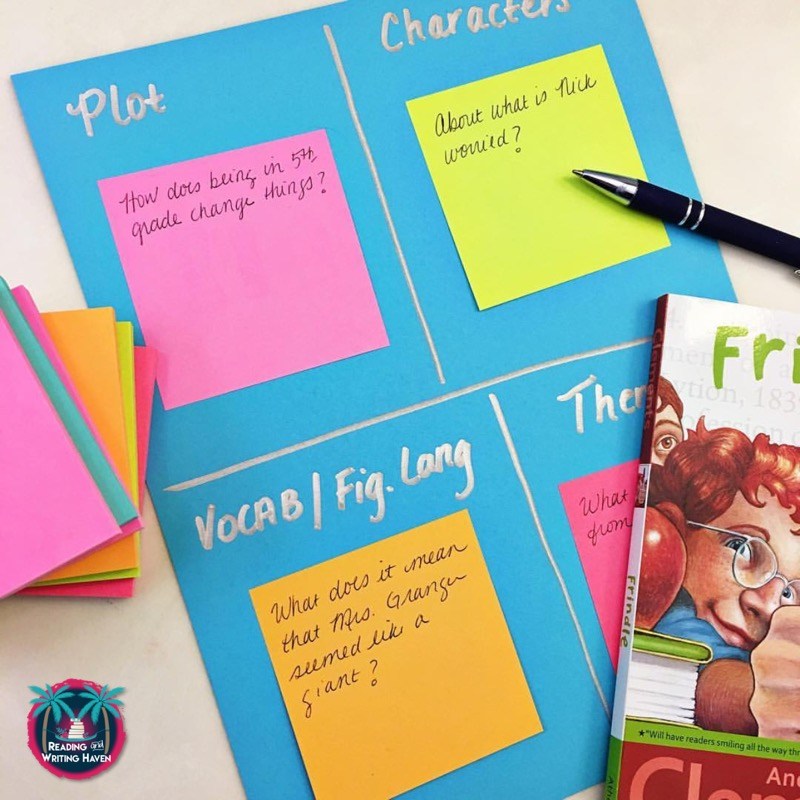

This is a strategy I learned from Jennifer Serravallo at a reading conference. The premise is pretty simple, and teachers can use it for both fiction or nonfiction texts. Have students divide their papers into four quadrants. Then, have them label each quadrant with a word like “plot,” “character,” “vocabulary,” or “theme.” If using the assessment for nonfiction, you could use terms like “main idea,” “key details,” “vocabulary,” and “author’s craft” or “text features.” Basically, use words and categories that relate to the standards you want to assess.

Then, decide which question you’d like to ask about the text. Try to space questions out so that you can pause periodically as you read. See an example below that I used with a group of 7th grade special education students as we read Frindle.

Choosing What to Teach

So, people ask about what they should teach when it comes to reading in secondary. My own approach is always to return to the standards and the students. Focus less on what literature is needed.

First, determine what whole-class skills students need to work on in order to meet the standards. Then, take into consideration individual student needs. Where do they overlap? Can you organize some small strategy groups to differentiate?

Deciding what literature you’ll need to meet students where they are matters. But, literature shouldn’t determine the learning objectives for the lesson or unit.

RELATED READING:

Getting to Know Your Readers

Balancing Whole-Class Novels and Independent Reading

A Reading Comprehension Strategy for Older Students

RELATED RESOURCE:

Regardless of the literature you select, these graphic organizers and scaffolded lesson plans will help students to practice behaviors and understandings inherent to the Common Core standards.