4 Essential Scaffolding Strategies for Middle and High School

Do you ever feel like you’re not sure what to do with the students who…fail vocabulary quizzes, struggle to write essays, find grammar challenging, or grapple with literary analysis? It can be a lot. Scaffolding strategies can help students complete complex tasks within their zone of proximal development. Build scaffolding strategies into your teaching units where necessary so that differentiation is more manageable and learning is more efficient.

Let’s take a look at four meaningful ways to do this in the middle or high school classroom. Each of the strategies below offers some content-specific suggestions, but all of them can be applied to any aspect of ELA.

1. GRAMMAR: TRY LAYERING

Students need to have multiple exposures to a topic or skill in order to truly learn it. Those exposures are most beneficial if they allow students different angles from which to understand the concept.

For instance, when teaching sentence structure, I begin with direct instruction, which includes modeling. From there, we do some whole class practice and then small group. Finally, I gradually release students to try applying the strategy to writing on their own.

With each practice opportunity, students are considering sentence structures from a different modality. The whole-class practice is visual and auditory. With small group activities, I can work in kinesthetic options, like manipulatives and sorts. Plus, I add real-world application and color-coding strategies. Students also enjoy games and logic-based activities, like mazes.

With the variety of learning opportunities, it’s simple to differentiate, and scaffolding strategies are naturally built into the unit.

Here is a post I wrote with extended tips for teaching and scaffolding sentence structure. Of course, the best way to scaffold grammar is to begin with a grammar sequence that naturally builds one skill upon the next.

2. VOCABULARY: USE BRAIN-BASED APPROACHES

The most common reason students don’t retain new vocabulary words, in my experience, is because their exposure to practice opportunities is limited. We can’t give students a list of ten words, tell them to “go study” the words, and then give them a quiz. That approach usually ends in memorization, not retention.

Many students benefit from brain-based approaches, like incorporating color, music, and associations. Even though I use these strategies with different ELA topics, I’m semi-obsessed with applying them to vocabulary. Students internalize new words most effectively when they interact with the words using brain-based learning.

If you’ve ever read The Core 6, you may be familiar with CODE. Basically, it is an acronym which means that students need to connect with new words, organize them into meaningful categories, deeply process the words, and exercise their understanding of that word.

To do this, I have a wide variety of instructional strategies as well as teaching resources that I use for a short bit daily, or as often as time allows. Visuals are one of the cornerstones of this scaffolding approach.

3. READING: SUPPORT WITH GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS

How often do you analyze the standards in depth? I’ve been trying to do it more, which has really helped me with scaffolding strategies. By trying to dig deep into what the standards are actually asking students to be able to do, I’m able to put myself in the position of a first-time learner. As I reflect upon how the standards are written, I try to break each one down into its smaller components.

Teaching reading in secondary is a complicated process. Teachers can use graphic organizers to scaffold literary analysis if we create them in a way that breaks down complex tasks into smaller ones. For instance, if students are analyzing how the setting of a story impacts other narrative elements, we could pose questions like these:

- What is the setting of the story?

- Identify the time, geography, culture, era, environment, weather, and population.

- How does the setting create an obstacle for the characters?

- In what ways does the setting establish the mood?

- How does the setting relate to the title?

- What part of the setting might be symbolic?

- How does the setting help to develop the theme?

After students have taken time to organize their answers via a graphic organizer, they will have the building blocks for a well-informed written or verbal response. Sometimes we jump straight from reading and annotating into responding, but graphic organizers can be the bridge that helps students organize and process their annotations into a well-organized written response.

One of the most powerful things we can do with scaffolding reading is helping students select books that are a good fit for them. Here are some additional thoughts about addressing gaps in reading comprehension in the secondary classroom.

4. WRITING: CHUNK ADVANCED SKILLS

Of all the tasks we ask students to do in English class, writing is probably the most frustrating for students. It’s a complicated process. Students have to reflect on a topic, analyze what they have read, organize the information logically, and synthesize what they know in order to create something new.

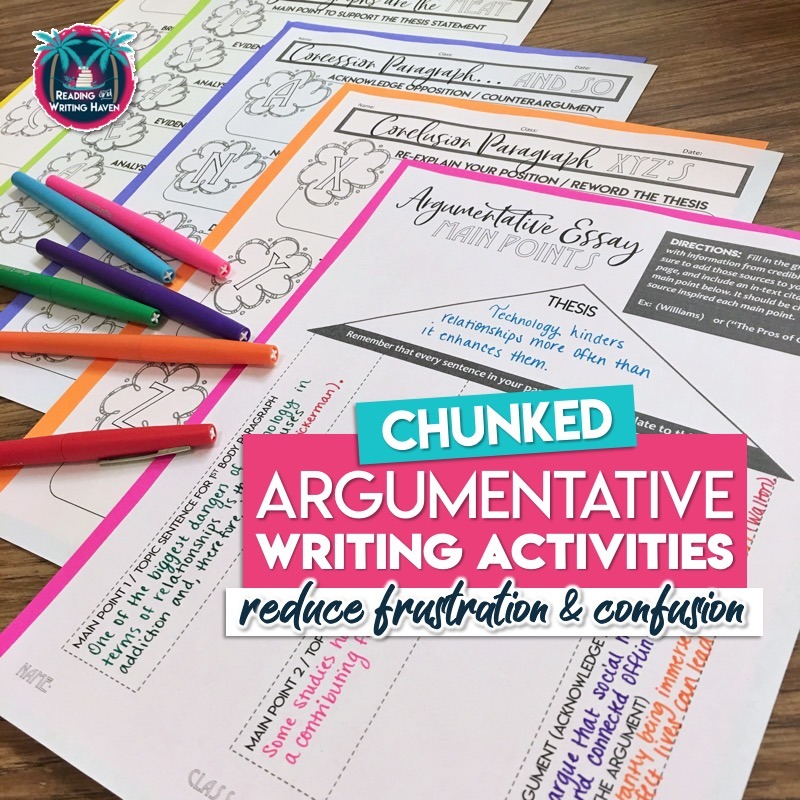

As I’ve worked with Title I students and co-taught classes at both the middle and high school levels, chunking has been the most effective way to scaffold writing. Consider the needs of your students. Can they handle analyzing an entire introduction paragraph at once, or do they need you to break down the individual components? I’ve done both…for different student needs.

When chunking writing, it’s important to provide feedback as soon as possible each step of the way so that students can revise and, in doing so, learn how to improve upon certain skills.

Of course, graphic organizers, modeling, color coding, and acronyms are staples I use to help chunk essay writing for students. Here is a unit example for argumentative writing.

Some people prefer not to give their students such a structured approach to writing, which is completely understandable. We just need to consider students’ readiness levels and make sure to provide students who benefit from more scaffolding with the tools they need to be successful.

Read more about scaffolding strategies for writing here and here as well as specific approaches for argumentative writing.

MONITORING TO REMOVE SCAFFOLDING

Of course, we should also be monitoring how much scaffolding our students need. While scaffolding doesn’t hurt students, it is important to continue pushing them toward independence little by little. Whenever I’m in doubt, I ask my students. They know what frustrates or confuses them! Students can help us figure out what scaffolding they need.

Instructional scaffolding just needs to be part of the way we teach. When we sit down to lesson plan, we need to ask ourselves how we can use scaffolding to differentiate for groups of students. Looking at a task through the lens of a first-time learner can help. Also, reflecting on each day’s lesson to identify areas where we might provide more support is invaluable.

I would love to see how you structure and pace your year. I find your style to be a nice balance of depth and variety. Have you ever posted or shared this?

Hi, Kristina! Thanks for your kind words. I have posted about a grammar sequence for the year as well as what I enjoy doing first nine weeks, but I haven’t posted about a general structure and pace for the whole year, mainly because I have switched grade levels a few times, and my structure and pace has changed over time due to adopting different teaching approaches and adapting for different groups of students. I will add it to my blogging topics list. What grade do you teach?