What is Meaningful Homework?

What is meaningful homework? In middle and high school, stereotypical visions of students weighed down by heavy backpacks and up all hours of the night completing packets and studying for large exams abound. Of course, those of us in education know this is typically not what an average homework load entails.

Still, schools are all over the board with the type and amount of homework they assign, ranging from none to quite a bit. Some parents worry about the homework load, and others think it’s a sign of a quality education.

With plenty of questions and not enough answers, I decided to do some research. Homework tends to be just “TOO…” sometimes…too much, too little, too easy, too frustrating, and even – too antiquated.

As I dug into my research question – What is meaningful homework? – I hoped I’d find a clear answer.

Well, I didn’t. There is not one correct answer for the homework dilemma. When I combine what I’ve learned with my own teaching experiences, it really depends upon your context, your students’ needs, your purpose, and much, much more. In this post, I’m writing about some of the key elements of my learning.

These findings are intended for secondary classrooms.

The Purpose of Homework

In order to tackle this huge research question, I needed to narrow it. So I started thinking about the purpose of homework. Why do we assign it?

Reflecting on my own mistakes, I thought about times I had over-planned my lessons. Too much to do in one class period? Just assign the rest as homework!

Then, there’s the facade of homework. If you aren’t assigning it, are you a rigorous teacher? Surely, a class students would learn something from would be assigning homework, right?

Of course, I also thought about the “tradition” of homework. As a student, I’d always been assigned homework. In almost every class! I remember filling in my student planner. Every day, I’d have a homework assignment written down after each class period I attended.

But, when I considered the “purpose” of each of these uses of homework, (over-planning? appearances? tradition?) I had to admit…none of those reasons benefits student learning. This realization brought me back to a narrower version of my original research question.

What is the purpose of homework?

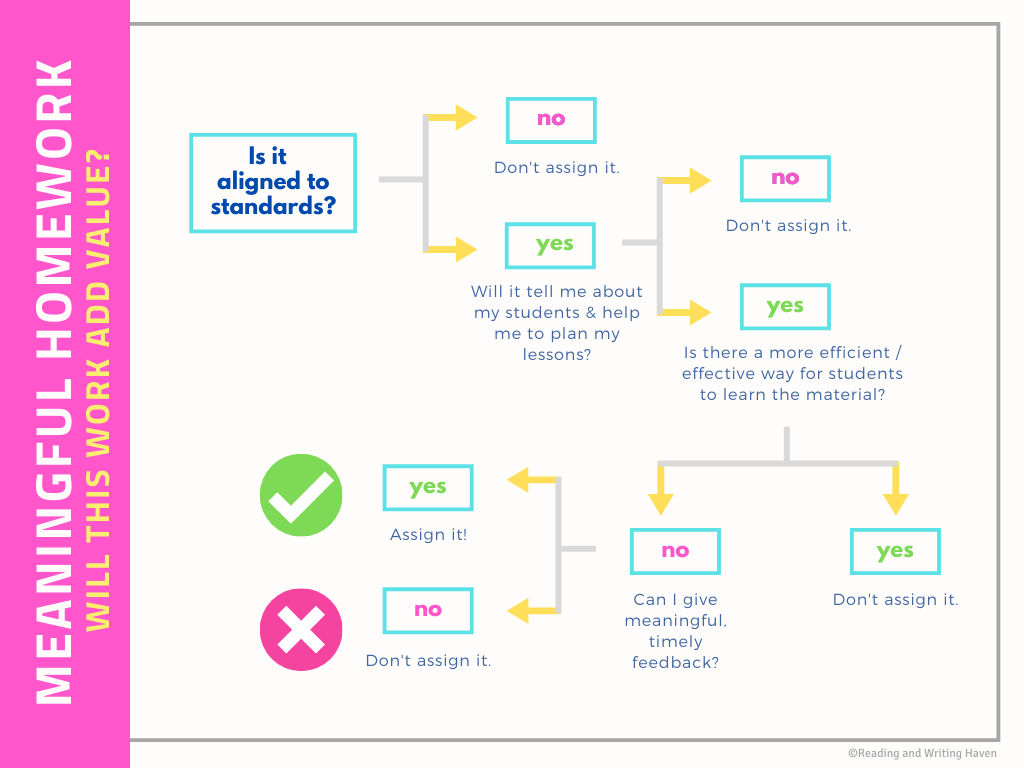

Using research from John Hattie and Robert Marzano, I was able to come to a strong conclusion. Meaningful homework should always add value to the learning process for teachers and students. And that has become my reflective mantra. Is it adding value?

Teacher Expertise and Meaningful Homework

Data-Driven Teaching

Meaningful homework should provide teachers with data to drive teaching. If I assign work, put it in a tidy binder-clipped pile, and then file it in the dark recesses behind my desk, what value is that adding to my teaching?

When students submit work, I want them to know that I’m using that work as data to make meaningful instructional decisions. That begins with standards alignment.

What types of questions or skills are students needing more practice with? Which areas are they already showing strength? Does the homework data indicate any subgroups need intervention or reteaching?

Sometimes this information is gathered as students are working on homework, and other times it’s gathered upon collection.

Once we have the data, homework is meaningful if we do something with it. We can make instructional decisions that impact the next day’s lesson or overall unit for the entire class or for small groups of students.

An Extension of Good Instruction

For teachers, meaningful homework is also an extension of good instruction. In other words, if we are maximizing our classroom teaching time, our homework will be more meaningful. For example’s sake, let’s consider the novel unit.

If we have students listen to an audio recording of a novel for forty-five minutes and then send them home to finish packets about the reading, we haven’t maximized our instructional time. Why are students spending the entire instructional period listening to a novel? Maybe it’s because they wouldn’t read the novel outside of class or because it’s too challenging for them to read independently. In both cases, using a shorter text for a mini-lesson in a reading workshop format would provide opportunities to maximize instructional time, teach standards, get to know our students as readers, and differentiate for learners based on what they need.

Teacher expertise – the decisions we make about what we are teaching in class and how we approach it will impact the quality of homework we assign.

Student Perceptions about Homework

For students, meaningful homework should enhance learning. Several key factors influence students’ attitudes toward homework.

Is it engaging?

While the sole purpose of homework is not to engage students, they are, of course, more likely to complete work they find engaging. We have to be careful with this one though because it’s easy to sacrifice the standards-aligned integrity of an assignment for sake of bells and whistles. One question I’ve started to ask is, “Can I make it more engaging?” The answer is not always yes, but simply reflecting on this question or brainstorming with a colleague or coach can help inspire new ideas.

Does it feel like busywork?

A deal-breaker for students is busywork. They can sense it coming a mile away. Busywork makes students question whether the homework is worth their time, and often, it angers or frustrates them. Crossword puzzles, tech-heavy assignments, and intricate coloring projects come to mind when I think of busywork. You, I’m sure, can add your own connections to that list.

Do they know why?

Sometimes, students perceive work to be busywork because they don’t understand the value of the assignment. If we frame the “why” for them, they’ll be part of the bigger picture.

Is it concise?

When creating homework assignments, we can also consider how long it will take students to complete. Doing the assignment ourselves is a good first step. For instance, when I first started with digital one pagers, I thought they would be something students could complete in one assignment. After doing the work myself, however, I had helpful insights about how to make it more concise. Chunking each step and pairing it with a reading-related mini lesson was going to be more concise for students, more beneficial for learning, and less overwhelming for all. It would be more respectful of students’ time.

With distance learning, meaningful homework most likely means less homework. Since students are already spending an unordinary amount of time in front of a screen, homework assignments should be concise, and – if possible – something that can be completed away from a device.

Does it allow for voice and choice?

Is there any way students can be part of the homework decision-making process? Building in options with choice boards, playlists, or differentiated tasks can help. Allowing them to choose their topics for writing assignments or select books for literature units, book clubs, and independent reading are sound choices as well. I’ve used exit tickets and entrance slips to allow students a way to decide what we do the next day. These are a natural part of reader’s and writer’s workshop.

Is it focused on critical thinking?

Students easily tire of lower-level skill assignments. Comprehension questions, grammar worksheets, writing vocabulary definitions. We can elevate thinking with homework assignments to engage students. Just for an example, focusing on higher-order thinking skills means moving from…

- vocabulary memorization to making image associations

- grammar identification practice to using grammar elements in writing or finding them in readings

- multiple choice comprehension questions to analyzing how themes relate to real life

Whenever possible, homework should be crafted so that students can be successful independently but so that they still find it interesting and intellectually challenging. For instance, sketchnotes are a naturally differentiated task students can use to process what they have learned away from the screen.

Will they receive feedback?

When students know they will receive feedback on their work, it makes homework more meaningful. They often wonder, Will the teacher even read this? And, I’m sure you’ve seen students who plug in random sentences, like the lines to the “Pledge of Allegiance” because they assume their work is not valuable enough to be read. Imagine toiling over an assignment, turning it in proud of your hard work, only to realize it will never be read or acknowledged. If it’s happened to you, you know how quickly that leads to disenchantment.

Ultimately, teachers are experts. If we know the homework we are assigning will benefit student learning and help us drive instruction…if we know it will be respectful of their time, home lives, and resources, it’s okay to assign work students don’t love. Cell phones, video games, and social media are difficult distractions to compete with. Even after we’ve done our best to create relevant, meaningful assignments, students may not want to thank us for assigning homework.

Building-Level Considerations for Homework

Meaningful homework conversations are beneficial topics for teams and departments to explore over the course of an entire year. Having intentional, reflective conversations is key.

Define Homework

Begin by defining homework. It’s not uncommon for educators to be on different pages. For instance, is it considered homework if it’s assigned near the end of the period and students are given time to work on it? If they use their time wisely, they should finish, but there are no guarantees. Is this homework? In my mind, it is, but homework conversations are more valuable when a common understanding is reached.

Cross-Subject Conversations

Together, teachers can explore how they can consider the homework load students experience throughout an entire day and work together to space out due dates for student stressors, like projects, research papers, and tests. Create a shared document the team can reference as they lesson plan.

Cultural Context

As a group, you can explore the cultural context of your school. Homework is not inherently bad or good, and its benefit always depends on how much your student body needs. If you work in a district where homework is never completed, assigning it and adding zeros to the grade book is detrimental to students.

Some students do not have access to technology at home, and with the recent increase of online learning, the digital divide and homework gap is widening. How can you identify whether students 1) are not willing, 2) are not able, or 3) are not organized enough to do their homework? And, what supports does your school or can your school put in place for students who do not or are not able to complete homework?

Involving Families

Conversations around how to involve families in the homework process are helpful as well. Teachers need parent partnerships and support to create environments where students can focus and prioritize school work. Assignments that extend to family and life are more authentic and relevant. Students can have conversations with their parents about themes in literature or add value to historical contexts. Always, we need to be sensitive to the diverse backgrounds of our students. We cannot expect them to complete work that requires resources and time families cannot provide.

Reflect on Research

Spend some time throughout the year finding and sharing research about homework. Analyzing research through the lens of what is right and true for your own situation can help you decide where you fall on the homework continuum. What does the research say? Why do people disagree? What existing beliefs might need to be highlighted or challenged?

The Continuum

Making these conversations specific is important. One way to do this is to come up with example homework assignments – research papers, word searches, flashcards, flipped lessons, etcetera – and have teams of teachers place them on a continuum from least to most meaningful. With most assignments, you’ll find that some teachers can think of a meaningful way to use that particular skill, and others can expose its disadvantages as a homework assignment. There is no “right” way to organize the lessons on a continuum. The value is in the conversation. Add a layer of fun by hosting an award ceremony following the continuum conversation. Here are a few example awards:

- Most relevant to life

- Best for spiral review

- Most engaging and effective

- Most likely to spark curiosity

- Biggest waste of time

Meaningful homework means rethinking the entire practice. Moving away from the routine of homework allows us to reflect on the what, when, and why to create strategic, relevant, and purposeful assignments. Meaningful homework is the result of intentional, regular reflective conversations that happen over time. Involving all stakeholders in the conversation at some level will result in decisions that are more informed and respectful of students’ needs.

FURTHER READING

If you’re looking for further reading about meaningful homework, you may find some of the sources I consulted while researching helpful. This list includes affiliate links.

- Five Hallmarks of Good Homework

- Homework Done Right

- Rethinking Homework

- The Case For and Against Homework

- Visible Learning

- Powerful Teaching

- Coaching Classroom Instruction

- The Core Six