7 Simple Secrets for Success with Discussion Based Literature Circles

Getting ready to begin student-led literature circles? Literature circles are the perfect opportunity to combine reading, writing, speaking, and listening in an authentic way! But, sometimes the broad nature and endless possibilities can lead to lack of sufficient structure…or over scaffolding the experience.

In this post, I’m sharing simple secrets for success with discussion based literature circles. So, if you have ever thought about Googling “how to make literature circle discussions better,” OR if you are ready to move beyond superficial classroom conversations about books, keep reading.

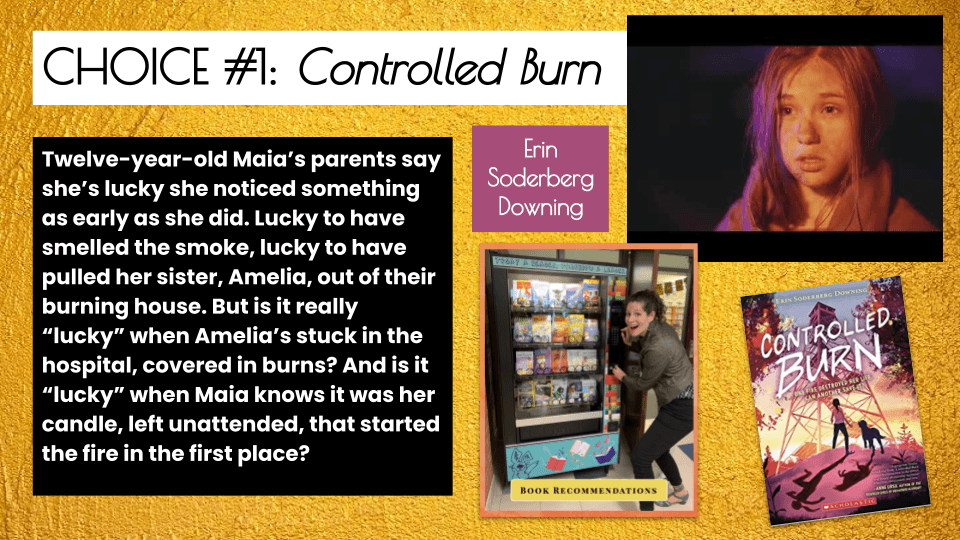

Secret #1: Sell the books!

Motivating authentic conversation about books requires students to want to read them! To begin a rich literature circle unit, spend part of a class period really selling the books. Specifically, try…

…creating a slideshow. Having a visual to share with students will keep them engaged. In the slideshow, include an intriguing snippet about or excerpt from the novel. Another fun idea is making an “If you like…, then you’ll really enjoy this book” recommendation.

…holding the book. Talk the book up! Tell students what you love about it, including anything noteworthy about the author, the cover, the point of view, or the length of the chapters. Then, put the book on display with the cover facing students.

…reading the first page. If the novel has a good hook, get students interested by reading the first page(s) out loud!

…showing a book trailer. Book trailers add another effective dimension to advertising a novel. Typically, people prefer to watch a video over reading something, so leverage that preference with book trailers.

Selling the book may not seem like an obvious connection to improving the quality of students’ discussions about the novel, but it does correlate! If students are looking forward to reading the book, they will be excited to talk about it, too.

Secret #2: Set a purpose!

The second secret ingredient for making literature circles a success is identifying learning purposes. In other words, identify the reading skills or author’s craft moves students need to focus on as they read.

Analyzing Signposts

For example, you may decide to introduce Notice and Note signposts, like contrasts and contradictions or words of the wiser. This may take the form of a mini lesson or a read aloud using an anchor text where you pause and model with think alouds. Why is the character doing that? How might answering this question help me to analyze character motivation or development on a deeper level? As students read their novels, they would then look for that same sign post and discuss it with their group at the next meeting.

Applying Reading Skills

Another option is to select specific reading skills for students to practice as they read. Summarizing, sequencing, inferencing, comparing and contrasting, questioning, visualizing, and making connections are just a short list of options! As students read, ask them to mark places where they applied these skills with sticky notes to make it easy to build them into literature circle discussions later. Or, let them jot down some thoughts on a graphic organizer.

Preparing to Write

If students are going to follow the literature circle unit with writing, set a purpose that allows students to select their topic and begin tracking evidence as they read. For example, students may write a cause and effect or problem and solution piece about a social issue in their novel. They may analyze cultural elements and assumptions or analyze the theme and its development. Each week, have students dedicate part of their literature circle discussion time to tracking evidence for their upcoming writing assignment.

Asking Interesting Questions

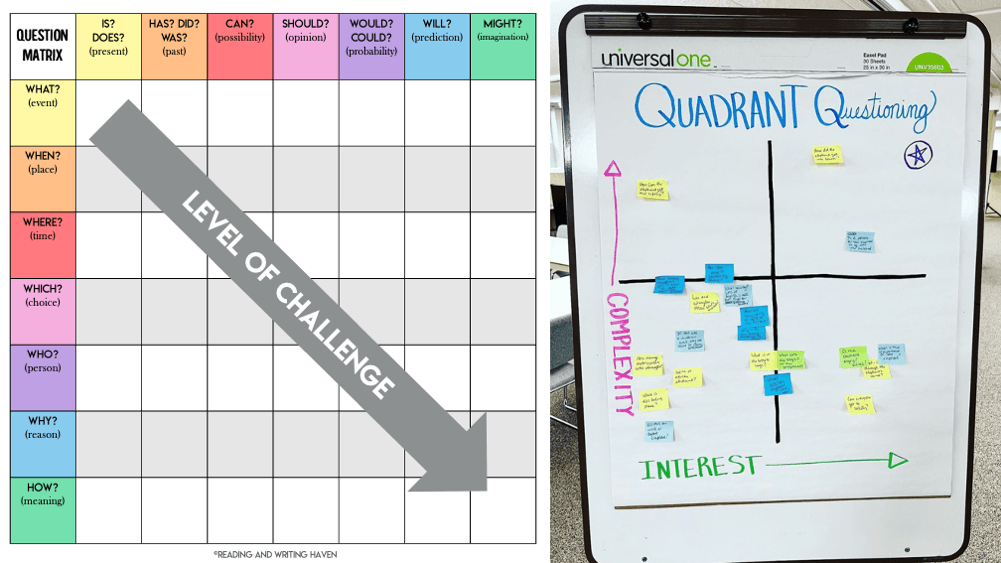

One of the reasons student-led discussions with literature circles can flop is due to a lack of interesting questions! We can teach students to write interesting questions by providing them with a few tools and modeling. One strategy I love is the Question Matrix, originally developed by Weiderhold and Kagan in 1995. You can see an updated visual below.

To model its use, pair it with an interesting visual like a picture or short clip, and watch as students’ thinking opens up! Have them write a couple of questions on a small sticky note. Then, explain the complexity and interest axis. Complexity refers to how well the question sparks critical thinking. For interest, the continuum represents how much the question inspires new ideas and promotes debate and discussion. Have students place their sticky notes on the quadrant where they believe their questions fit best.

Then, as a class, discuss any trends. Are the questions commonly in the lower left hand quadrant? Do low interest, low complexity questions lead to engaging student-led literature circle discussions? Is the photograph interesting, which sparks higher-level questions? How can students move beyond superficial, uninspired questions like What do you think will happen next? to ones that invite meaningful conversation by using the question matrix?

Secret #3: Let students make the reading schedule!

Formal roles during literature circles get stale quickly. Think…the literary luminary, the vocabulary enricher, or the discussion director. I tried implementing these roles when I first began literature circles because I thought they would hold students accountable for reading and provide an opportunity for everyone to speak.

I was wrong.

Students didn’t read just because they had a “role” sheet to complete. And, the rigidity of the roles made the discussions less authentic than they could have been. So, I started looking for different ways to honor ownership and choice.

When students meet to discuss their books, everyone speaks. But, the focus of the conversation is based on real discussion skills. For example, can students build onto someone’s comment instead of ping-ponging around the circle? Can they respectfully counter an idea presented by a classmate? Do they know how to invite friends who haven’t spoken much into the conversation? And, can they ask questions their peers want to discuss?

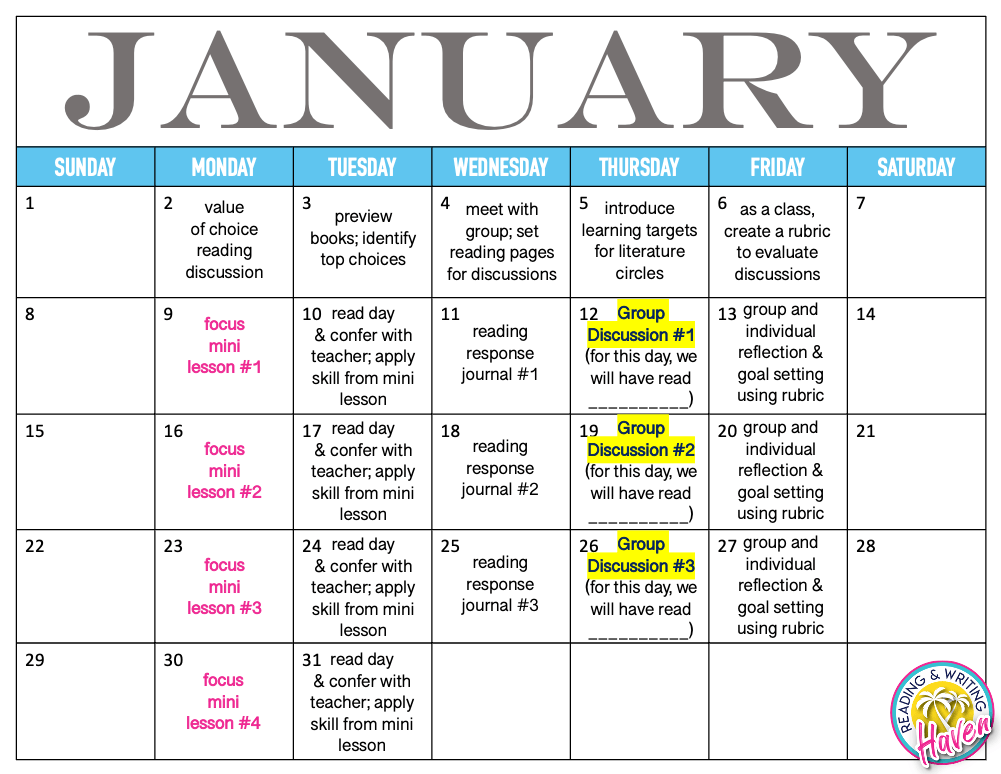

As students prepare for this type of conversation, I invite them to create their own reading calendar. In order to have a rich conversation, students need to read the book! Giving students a voice in how many pages or chapters they want to read for each discussion date increases the likelihood that they will read! When a group makes a decision together, everyone counts on one another to make it work.

Secret #4: Build in reading days!

As you can see in the calendar above, it’s helpful to build in reading days. Protecting in-class reading time shows students that reading is a priority, and they are more likely to read their book at home if they get sucked into the plot or befriend the characters during school hours. And, if students read their books, discussions will be better.

Plus, in-class reading time opens up opportunities for us to confer with our readers! We can sit with each students for a few moments to talk about the book. During reading conferences with literature circles, I recommend focusing on whatever mini lesson strategy, skill, or concept students should be applying to their book as they read.

For example, if the most recent mini lesson was about making inferences about characters based on their actions and words, ask students to show you an example of a recent inference they have made! To make these conversations flow more smoothly, have students record their inferences (or whatever skill they are working on) on sticky notes as they read.

Reading conferences make for perfect formative assessments so you can track students’ progress on reading standards without taking work home!

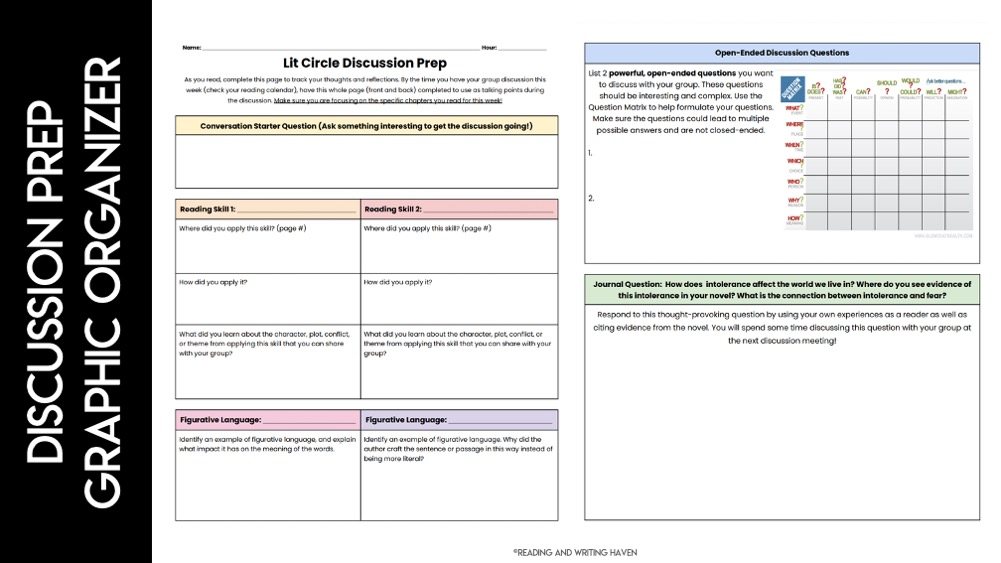

Secret #5: Build in discussion preparation days!

It’s also helpful to plan discussion preparation days into the calendar. Do you want students to craft questions to discuss with their peers? When should they do that? Should they reference the question matrix as they compose their questions?

Another preparation idea is to have students select quotes that stand out to them or evidence that shows the development of a theme or the change in a conflict.

Are there certain questions you will want all groups to discuss, regardless of the book they are reading? Doing so can provide a common grounding place for whole class discussion following the small group experience. Consider this example:

A coming of age story is one in which the main character experiences a shift in perspective, a greater realization of their place in the world, or a deeper understanding of how their personal actions impact others and the future. In what ways does your novel fit the description of a coming of age story?

I also like to give students time to write in response to a specific question before a discussion day. Journaling helps students to process their thinking, which, in turn, improves the quality and depth of their student-led literature circle discussions.

When students have time to prepare their thinking in advance, they share more during discussions with peers. Building in preparation days – whether you use a graphic organizer, a reading journal, a vlog, or a blog (anything works!) will make literature circles more productive.

*PRO TIP 1: Reading and discussion days are not lost instruction opportunities! On these days, we have the flexibility to sit one-on-one with students or meet with them in small groups to provide them the personalized instruction they need. This is differentiation at its finest!

*PRO TIP 2: Keep a predictable pattern with the way you organize days on the literature circles calendar so students grow accustomed to the sequence and fall into a comfortable rhythm.

Secret #6: Teach students how to discuss!

I’ve found that students do a far better job of having fluid literature circle discussions when I explicitly teach them what it should look and sound like to carry on an academic conversation about a novel. How can we do that?

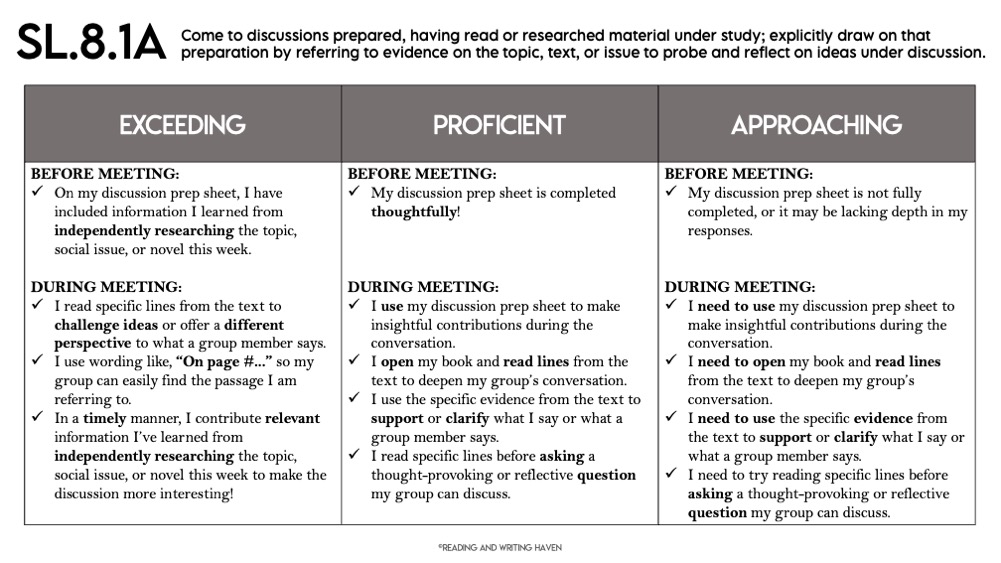

I begin with the standards. They show me the learning targets students need. For example, SL.8.1a reads like this: “Come to discussions prepared, having read or researched material under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evidence on the topic, text, or issue to probe and reflect on ideas under discussion.”

With students, we discuss and come to a consensus about what it would look like to be successful with this standard. Usually, we land with a list of identifiable skills like this:

- I have my discussion prep sheet completed before the group meeting.

- During the discussion, I open my book and read specific lines from the text that support what I say or what a group member says.

- During the discussion, I open my book and read specific lines from the text that challenges or offers a different perspective to what a group member says.

- During the discussion, I open my book and read specific lines before asking a thought-provoking or reflective question my group can discuss.

Then, we review this list before the discussion. As groups talk, I sit with each one for about ten minutes (not all groups can discuss at the same time) so that I can provide feedback and model what these skills can look like in practice. Following the conversation, we reflect on how our literature circle discussions went in light of the success criteria for our learning target(s). Then, we set a goal for the next discussion.

Each week, we add on another standard and new skill focuses, while spiraling in the skills from the previous week. Over time, students do much better with having a deep conversation about their books. They enjoy having specific skills to focus on that make speaking and listening goals tangible and measurable.

Secret #7: Generate rubrics with students!

Pictured above, you can see an example of a student-generated rubric. I like to do this for each discussion skill we focus on because it means students have more ownership in their learning, and they understand the expectations for proficiency better.

To begin, identify the standard (as mentioned above under Secret #6). Then, in small groups, have students generate a list of what it would look or sound like to be proficient with that standard. As a class, refine the list. Once you have identified the evidence or criteria for proficiency, ask students to think about what it would look like to be exceeding proficiency. How could they go above and beyond with this standard by focusing on quality of their contributions to the discussions instead of quantity?

For example, show students that the standard doesn’t technically ask them to offer different perspectives for their group to consider. But doing so would elevate the depth of the conversation. Avoid adding language to the rubric that pigeon holes students into contributing 10 times to be exceeding as opposed to six times to be proficient. Quality conversations really aren’t about the number of contributions as they are the natural flow and level of thinking.

Once the rubric is crafted, use it to set reflect on progress and set goals. Make sure students self-assess their contributions with this rubric after each discussion!

And those are my seven secrets to quality student-led discussions during literature circles! By chunking speaking and listening skill focuses, scaffolding the preparation process, opening space to read and confer during class, providing a predictable rhythm, and offering feedback based off of a rubric everyone agrees upon, you’ll see conversations soar.

Are you loving the ideas in this post? You can grab free templates for everything pictured in the resource library for my blog, an exclusive perk for subscribers. Not a subscriber? It’s easy to get on my list by filling out the form below! Then, look for an email from me to confirm that you want to hear more from me! Access to my resource library and these templates will follow.

READ NEXT:

- 15 Fun Ways to Freshen Up Your Independent Reading Program

- Full-Choice Classroom Book Clubs: A How-to Guide

- Reading Instruction: Deciding What to Teach